Lightening the cutaneous and emotional burden of melasma: Cysteamine’s role

Source: https://www.aad.org/

Melasma is a frustrating disorder for patients and practitioners alike. Facial gray-brown patches may cause psychosocial distress and embarrassment, thereby diminishing quality of life. (1) Melasma most frequently occurs in women with Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI with an average onset between 20-30 years of age. Exacerbating factors of melasma include pregnancy, hormonal contraceptives, ultraviolet light exposure, and autoimmune thyroid disorders. (2,3) The pathogenesis is enigmatic, but increased stem cell factor, which binds the tyrosine kinase receptor c-kit, alterations in the Wnt signaling pathway, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, barrier dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, increased mast cells, fatty acid abnormalities, and increased vascularity related to VEGF have all been implicated. (1)

Although triple combination therapy (hydroquinone/fluocinolone/tretinoin) is considered the premier topical treatment for melasma, the controversy regarding potential carcinogenicity of hydroquinones (an increased skin tumor incidence has been reported in mice treated dermally, however, there is no information available on the carcinogenic effects of hydroquinone in humans), (4) and the risk of exogenous ochronosis, have propelled the search for alternative treatments.

The number of therapeutic options is dizzying — Austin et al identified 35 original randomized clinical trials using azelaic acid, cysteamine, epidermal growth factor, hydroquinone (liposomal-delivered), lignin peroxidase, mulberry extract, niacinamide, Rumex occidentalis, triple combination therapy, tranexamic acid, 4-n-butylresorcinol, glycolic acid, kojic acid, aloe vera, ascorbic acid, dioic acid, ellagic acid and arbutin, flutamide, parsley, or zinc sulfate for melasma. The authors concluded that cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid received strong clinical recommendations for the treatment of melasma.

This commentary focuses on cysteamine for the treatment of melasma.

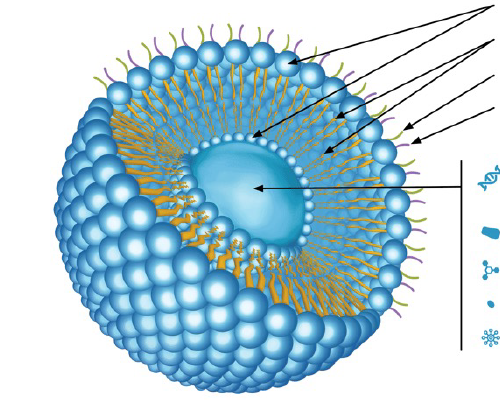

Cysteamine (2-mercaptoeth-ylamine) hydrochloride has been known as a potent depigmenting agent for more than 40 years. It is a product of cysteine metabolism, acting as an intrinsic antioxidant, protecting against ionizing radiation and serving as an antimutagenic agent (compared to hydroquinones, which are cytoxic and mutagenic in some animal models). Cysteamine is a thiol compound, inhibiting tyrosinase and peroxidase involved in melanogenesis. The molecule also scavenges dopaquinone in the melanin pathway, chelates iron and copper, and increases intracellular levels of glutathione (which is associated with the shift of eumelanogenesis to pheomelanin synthesis). Being a thiol compound, cysteamine is associated with an offensive odor, which obviated its cosmetic use; only recently has new technology combated this odor, allowing a cream to be developed for clinical application. Mansouri et al, in a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind study, demonstrated that cysteamine showed significantly greater efficacy than placebo in the treatment of melasma at 2 and 4 months as determined by investigator’s global assessment and patients’ viewpoints. (6)

Studies comparing cysteamine to hydroquinone have been performed. Lima et al performed a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded clinical trial on 40 women with facial melasma utilizing 5% cysteamine or 4% hydroquinone (HQ) on hyperpigmented areas for 120 days. Patients were assessed at the inclusion and after 60 and 120 days of treatment for mMASI (modified melasma area severity index), MELASQoL (melasma quality of life scale), and the difference in colorimetric luminosity between melasma and the adjacent unaffected skin. The Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale was used to assess the difference in the appearance of the skin through standardized photographs. The mean reduction of the mMASI scores was 24% for cysteamine and 41% for HQ (P = 0.015) at 60 days, and 38% for CYS and 53% for HQ (P = 0.017) at 120 days. The photographic evaluation revealed up to 74% improvement for both groups, without statistically significant difference between them. The MELASQoL score showed a progressive decrease for both groups over time, despite the greater reduction for HQ after 120 days. Colorimetric assessment disclosed progressive depigmenting in both groups, without statistically significant difference between them. No severe adverse effects were identified in either group. Erythema and burning were the most important local adverse effects with cysteamine, although their frequency did not differ between groups (P > 0.170). The authors concluded that cysteamine is safe, well-tolerated, and effective, despite its inferior performance to hydroquinone in decreasing mMASI and MELASQoL in the treatment of melasma. (7)

Nguyen et al performed a randomized, double-blinded, single-center trial with 20 recruited participants who were given either cysteamine cream or hydroquinone cream for 16 weeks. The primary outcome measure was a change in the mMASI. Quality of life at baseline and week 16 as well as standard digital photography at each follow-up visit was assessed as secondary outcome measures. At week 16, 14 participants completed the study with 5 participants in the cysteamine group and 9 patients in the hydroquinone group. In the intention to treat analysis there was a 21.3% reduction in mMASI for the cysteamine group compared to a 32% reduction in the hydroquinone group. The difference between groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.3). Hydroquinone cream was generally better tolerated that cysteamine cream. The authors suggest that topical cysteamine may have comparable efficacy to topical hydroquinone, thereby providing a possible alternative to patients and clinicians who wish to avoid or rotate off topical hydroquinone. (8)

Cysteamine is readily available on the internet. In an unscientific survey, there is a range of reviews from 5 star (“This product delivers exactly what is promises. In just 3 weeks the results are obvious and amazing. I thought I was going to have to live with discoloration for the rest of my life. I am confident with my skin for the first time in 3 years.”); 3 stars (“I was very disappointed in this cream at first. I was frustrated because I wasn't seeing any results. AND IT SMELLS AWFUL. I used up a whole tube and saw no difference. I sucked it up and bought another tube because their case study pictures were so impressive. I’m in my 12 or 13th week using this cream and I am pretty impressed. My melasma is lightening up nicely. It took about 12 weeks for me to notice a change. Takes a while to see results, but this cream does work. Stinks...but it works...LOL”); to 1 star (“No change to age spots. Still there. :-( Might work for others — It just didn’t work for me”). The tally of 25 Amazon reviews for this brand (accessed March 16, 2021) was 5 stars [8], 4 stars [4], 3 stars [1], 2 stars [2], and 1 star [8].

It is difficult to reach any conclusions on something I have never prescribed yet, other than the realization that cysteamine may offer some benefit for selected patients who do not wish to be treated with hydroquinone products. Inevitably there will be more studies forthcoming with combination products with cysteamine as part of the mix. For now, at least there is another option that at least has the potential to lighten the skin and spirit of those afflicted with melasma.

Point to Remember: Cysteamine may be an alternative for some patients with melasma where the use of hydroquinone is either contraindicated or not desired.

Our expert’s viewpoint

- Seemal R. Desai, MD, FAAD

- Founder & Medical Director

- Innovative Dermatology

- Clinical Assistant of Professor

- Department of Dermatology

- The University of Texas Southwestern

Melasma is a chronic vexing disorder of hyperpigmentation that can affect both females and males. It is critically important that patients understand that melasma is something that is not necessarily curable, but rather a skin disease that is controllable using a variety of therapeutic options. In fact, in my practice, which focuses on disorders of pigmentation and skin of color, melasma is never a condition that I treat with simply one therapeutic tool. This can often represent a challenge, since topical skin lightening, for example, is still dominated by prescription-based therapies centered around hydroquinone. So, you have a perfect storm — a chronic relapsing condition requiring multiple tools in your toolbox including a workhorse (i.e., hydroquinone) that has its own limitations preventing long-term use. Repeatedly, the question comes up both from colleagues, patients and even rhetorically — what else can one do?

That is where non-hydroquinone based topicals come into play. Off-label use of other tyrosinase enzyme acting agents, like azelaic acid, kojic acid, and others is a very significant part of my melasma algorithm. Oral polypodium leucotomas, with its antioxidant and UV benefits, plays a role. Topical cosmeceuticals like Vitamin C, topical tranexamic acid, topical cysteamine therapy, and other botanicals have become important alongside off-label oral tranexamic acid for recalcitrant cases. As discussed in this DWI&I commentary, cysteamine is an ingredient that has been around for a long time, but only now are we starting to incorporate it into our pigmentary disease discussions. All of this goes without saying, that broad-spectrum UV sunscreen topically is the number-one therapeutic recommendation no matter what other ingredients of the recipe you decide to use.

As we continue to research more and more about the pathogenesis of melasma, we find that the layers of the onion continue to peel. A disease which was once thought to be singularly linked to increased melanin, is now a disorder that has an increased vascular component due to VEGF and other factors. These include increased dermal mast cells, basement membrane alterations, UV-induced epidermal changes, and more. This is an exciting time for pigmentary diseases, and skin of color dermatology in particular.

- Jusuf NK, Putra IB, Mahdalena M. Is There a Correlation between Severity of Melasma and Quality of Life? Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019 Aug 25;7(16):2615-2618. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.407. PMID: 31777617; PMCID: PMC6876811.

- Kagha K, Fabi S, Goldman MP. Melasma’s Impact on Quality of Life. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Feb 1;19(2):184-187. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.4663. PMID: 32129968.

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, Abediankenari S, Moosazadeh M. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Nov;58(11):1231-1238. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14497. Epub 2019 May 31. PMID: 31149743.

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/hydroquinone.pdf (accessed March 15, 2021)

- Austin E, Nguyen JK, Jagdeo J. Topical Treatments for Melasma: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X. PMID: 31741361.

- Mansouri P, Farshi S, Hashemi Z, Kasraee B. Evaluation of the efficacy of cysteamine 5% cream in the treatment of epidermal melasma: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial.

- Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13424. Epub 2015 May 29. PMID: 25251767.

- Lima PB, Dias JAF, Cassiano D, Esposito ACC, Bagatin E, Miot LDB, Miot HA. A comparative study of topical 5% cysteamine versus 4% hydroquinone in the treatment of facial melasma in women. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-1536. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15146. Epub 2020 Aug 31. PMID: 32864760.

- Nguyen J, Remyn L, Chung IY, Honigman A, Gourani-Tehrani S, Wutami I, Wong C, Paul E, Rodrigues M. Evaluation of the efficacy of cysteamine cream compared to hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma: A randomised, double-blinded trial. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13432. Epub 2020 Sep 27. PMID: 32981068.